20th century: big ideas and the first patent

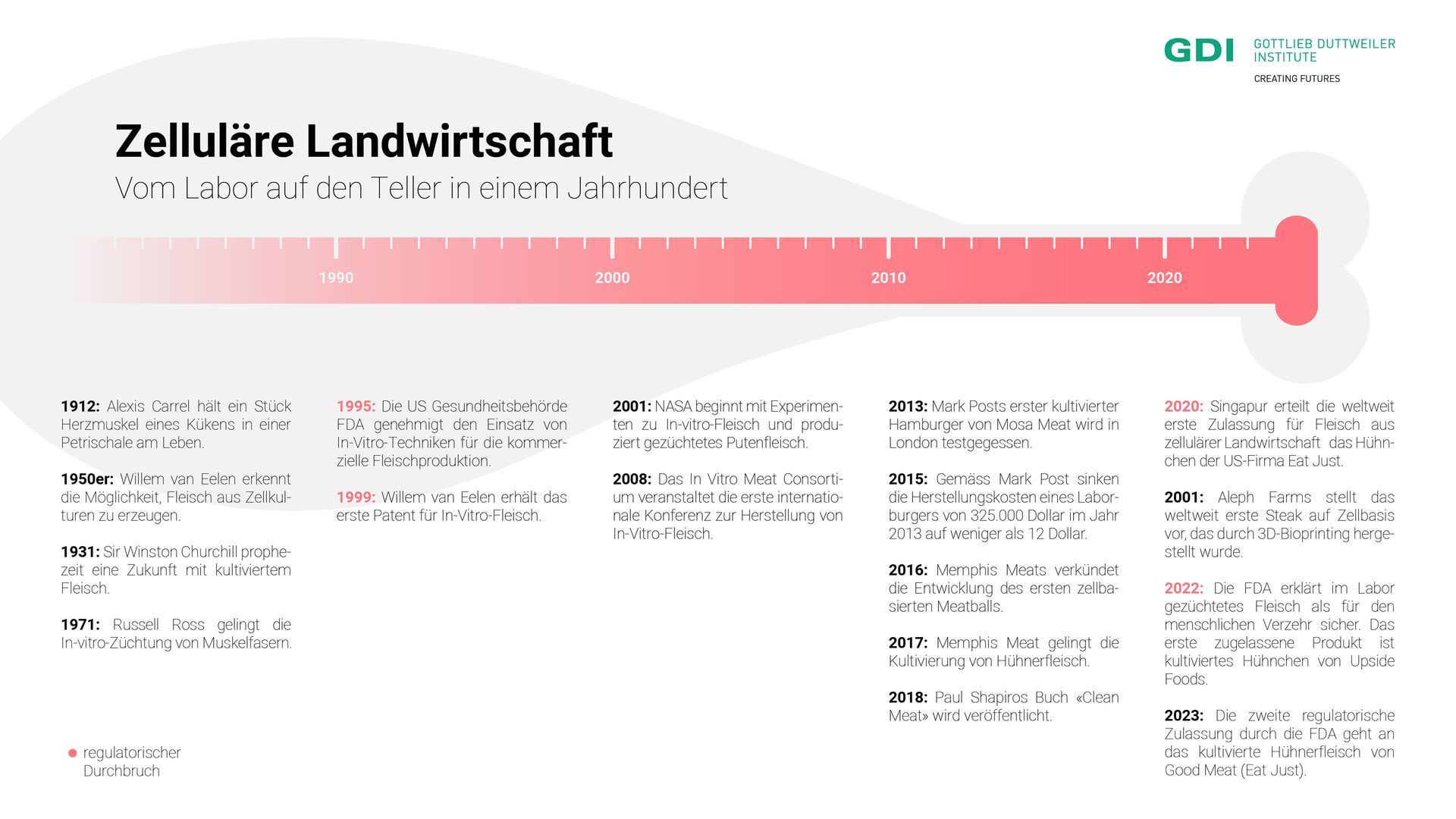

The story of cellular agriculture began in 1912. At that time, French surgeon Alexis Carrel successfully kept a piece of chicken heart muscle beating in a petri dish. This demonstrated that muscle tissue could remain alive outside the body when supplied with suitable nutrients. Many years later, in the early 1950s, Dutch researcher Willem van Eelen had the idea of using cell cultures to produce meat products. However, it wasn’t until 1999 that van Eelen’s discovery was patented, after the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of in vitro techniques in 1995. From then on, commercial meat production in the lab became permissible.

21st century: startup foundations, prototype development, and regulatory approvals

In the 2000s, the once-theoretical ideas suddenly became tangible. Lab-grown meat was no longer science fiction but a reality. NASA conducted successful cell culture experiments using cells from goldfish and turkeys, seeing this technology as a potential means of providing food for astronauts during long space missions.

2013 marked a turning point when Dutch pharmacologist Mark Post, from the company Mosa Meat, tasted his lab-grown burger live on television. The cost of the patty? $325,000. After that, development accelerated significantly. Startups were founded, investments were made, the price of cultured meat dropped by several orders of magnitude, and new product developments were continuously introduced. Startups worldwide presented lab-grown chicken, bacon, fish, pork and seafood.

For a long time, these products remained prototypes. Although American entrepreneur Josh Tetrick, founder of Eat Just (formerly Hampton Creek), announced in 2018 that his lab-grown chicken would be available by the end of the year, reality differed. It was only in December 2020 that the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) announced its approval for the sale of Eat Just's lab-grown chicken in Singapore. This made Singapore the first country to grant regulatory approval for meat from cellular agriculture.

The United States followed suit in 2022. The FDA declared Upside Foods' chicken "safe to eat." In 2023, they did the same for Good Meat, the CellAg division of Eat Just. Although these products are not yet available for purchase, and it remains unclear exactly when they will be, these decisions bring the USA closer to the availability of lab-grown meat in restaurants and supermarkets.

Meanwhile, the first approval in Europe is still pending. Although the Dutch company Mosa Meat was the first to introduce its lab-grown burger to a broad audience, Europe is taking a slower regulatory approach compared to Singapore and the USA. Italy has even taken a different direction: In March 2023, the Italian government passed a law prohibiting the use of lab-grown food and feed to protect the country's agricultural heritage. It may take several more years for these products to become available in Europe.

What’s next? Patent wars or open-source collaboration?

Lab-grown meat is intended to be an alternative to conventionally produced meat, aiming to not only protect animal welfare but also reduce the substantial environmental impacts of industrial meat production.

However, it also involves a significant amount of money. A report by The Good Food Institute stated that nearly $3 billion was invested in proteins from cellular agriculture between 2013 and 2022. Creating lab-grown meat requires intensive and expensive research and development. CellAg companies seek to protect their intellectual property through patents, with the goal of later licensing their technologies to other manufacturers. For example, Eat Just purchased van Eelen's very first patent after his death. Startups like Memphis Meat, Shiok Meats or Cult Food Science have also filed their own patents or already received them.

Instead of erecting market barriers with patents, an open-source approach for greater democratisation of the industry and increased participation is also possible. New Harvest is a sponsor-funded research institute based in New York that, in collaboration with the Slovenian Institute for Development of Advanced Applied Systems (IRNAS), is building a low-cost, modular open-source bioreactor for the cultivation of in vitro tissue. Their aim is to improve global access to research tools for cellular agriculture and advance the scientific development of lab-grown meat.

the international life sciences company Thermo Fisher, they are developing a system that can analyse hundreds of thousands of potential inputs for growth media, cell preparations, and scaffolds. This data will be made available to all companies in the industry to help them find the optimal components at the lowest cost. By building supply chains and distribution networks for a variety of products, not just one company, significant economies of scale can be achieved. This process, along with many other partnership and research projects, brings the goal of price parity between lab-grown and traditional animal agriculture products closer than ever before.