Der nachfolgende Text basiert auf einem Auszug aus der GDI-Studie «Prävention im Umbruch», die über unsere Website bezogen werden kann.

GDI: Inwiefern fliessen gesundheitliche Überlegungen in der Stadtplanung mit ein?

Villadsen: Gesundheit spielt in vielerlei Hinsicht eine wichtige Rolle bei der Stadtplanung. Dabei geht es uns darum, gesundes Verhalten möglichst zu vereinfachen. In Kopenhagen fahren beispielsweise viele Menschen mit dem Fahrrad. Nicht in erster Linie, weil es gesund ist, sondern weil es am einfachsten und schnellsten ist, sich mit dem Fahrrad fortzubewegen.

Viele Städte sind aber noch von den Modernisten der 50er, 60er und 70er geprägt, welche die Städte so ausgelegt haben, dass Wohnen, Arbeit, Freizeit räumlich stark separiert sind und man mit dem Auto von einem zum anderen kommt. Das führt nicht nur zu mangelnder körperlicher Bewegung. Auch findet kaum sozialer Austausch statt, wenn Menschen mit dem Lift von der Einstellhalle direkt vor ihre Wohnungstüre fahren. Die Menschen sind dadurch einsamer, was ebenfalls sehr ungesund ist. Heutzutage versuchen wir, wieder eine Vermischung herzustellen. So wie etwa in der 15-Minuten-Stadt. Das fördert nicht nur die Bewegung, sondern auch den sozialen Austausch.

Wie soll man sich konkret städtebauliche Interventionen zur Gesundheitsförderung vorstellen?

Ein schönes Beispiel, an dem wir beteiligt waren, ist ein Projekt in London, wo es um sogenannte «Food Deserts» ging – Orte, wo es kaum Möglichkeiten gibt, gesunde Lebensmittel zu finden. Etwa im Umkreis einer Schule. Die Läden in der Nähe hatten wenig Gesundes. Der McDonald’s war der einzige Ort, wo sich die Jugendlichen länger aufhalten konnten, ohne ständig zu konsumieren und Geld auszugeben.

Um dem Problem zu begegnen, arbeiteten wir mit den Einkaufsläden zusammen, damit diese mehr gesunde Lebensmittel im Sortiment aufnahmen. Andererseits schufen wir einen öffentlichen Raum, wo man das Gekaufte essen, sich aber auch ohne Konsumationspflicht aufhalten kann. Dieser Ort wurde mit den Jugendlichen zusammen gestaltet. Ganz wichtig ist ihnen bei einem solchen Gestaltungsprozess, dass Ort und Nahrung Instagram-tauglich sind. Durch Food-Trucks, die wir auch dorthin aufgeboten haben, wurde das Angebot zusätzlich bereichert. Sowohl kulinarisch wie auch in Sachen Social-Media-Tauglichkeit. Auch kamen dadurch zunehmend mehr andere Menschen, die in der Nähe arbeiteten oder lebten, zum Mittagessen zu diesem Platz. Damit wurde wiederum eine gewisse soziale Vermischung erreicht.

Ein anderes Beispiel ist die Uferpromenade in Shanghai. Das sind 45 Kilometer durchgängiger öffentlicher Raum. Hier macht es Spass, Fahrrad zu fahren, zu spazieren und andere Menschen zu sehen. Auch das gehört nun zu den meistfotografierten Orten in ganz Shanghai und wurde gerade in Zeiten von Corona als öffentlicher Ort besonders wichtig. Interessant ist, dass in China 70% der Bevölkerung über kein Auto verfügt. Im Gegensatz zu Europa ist hier die Herausforderung nicht, die Leute zum Fahrradfahren zu bringen, sondern, das gesunde Mobilitätsverhalten aufrechtzuerhalten.

Das klingt alles sehr überzeugend. Was sind aber die Hürden, die man für ein solches Projekt zu überwinden hat?

Zunächst ist da das Argument der Kosten. Neue Infrastruktur aufzubauen, kostet nun mal etwas. Aber eine Studie in Kopenhagen hat kürzlich gezeigt, dass die Stadt mit jedem gefahrenen Fahrrad-Kilometer Geld spart. Die Fahrrad-Infrastruktur ist günstiger als diejenige für Autos. Menschen stehen weniger lange im Stau, was auch volkswirtschaftliche Kosten sind. Dazu kommen die Kosten, die man einspart, wenn man eine gesündere Bevölkerung hat.

Die Einsparungen tauchen aber evtl. andernorts auf. Ein Verkehrsamt hat zunächst mal wenig Anreize, Geld auszugeben, welches dann im Gesundheitswesen eingespart wird. Solange aber Verkehr, Wohnungsbau, Umwelt oder Gesundheit von unterschiedlichen Organisationen einer Stadt geregelt werden, die wenig miteinander sprechen, werden Massnahmen, welche übergreifende Effekte haben, kaum angegangen. Man kann sagen, dass auch hier eine Vernetzung notwendig wäre.

Die strenge Separierung der Modernisten hat sich also nicht nur in der Architektur niedergeschlagen, sondern auch in der Art, wie wir eine Stadt organisieren. Nicht nur in der Organisation der Ämter. Auch viele Regulierungen stammen noch aus dieser Zeit und stehen damit auch dem Ausbruch aus dem Status quo hin zu lebenswerteren Städten im Weg.

Studie, 2021 (kostenloser Download)

Sprachen: Deutsch, Englisch

Format: PDF

Im Auftrag von: Curaden

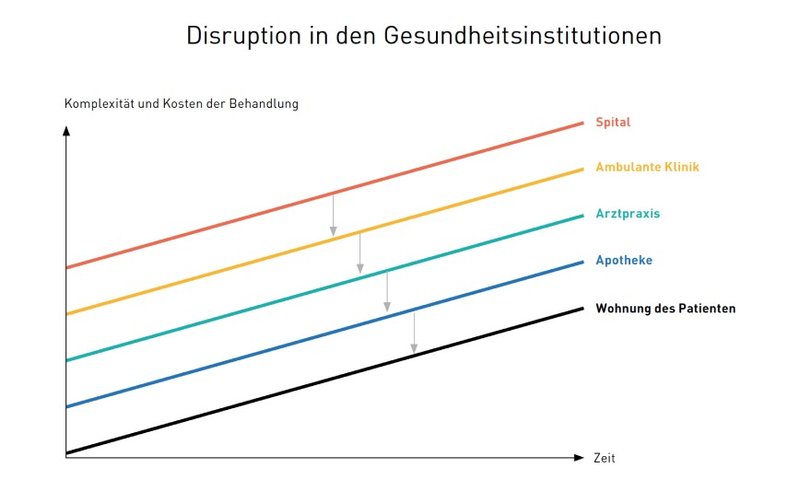

Infografik: Wie KI das Gesundheitssystem neu sortiert

Das Gesundheitssystem erfährt eine fundamentale Umwälzung. Präzisere Daten und künstliche Intelligenz ermächtigen Patienten und Pflegepersonal, Analysen und Behandlungen durchzuführen, die früher nur von Spezialisten bewältigt werden konnten. Verschwinden dadurch Arbeitsplätze?

«Präventionsarbeit wird nicht nur wichtiger, sondern auch wirkungsvoller»

Die Pandemie hat viele Gewohnheiten unseres täglichen Lebens verändert. Davon waren auch gesundheitsfördernde Verhaltensweisen betroffen. Wie sehr, sehen Sie im folgenden Vortrag von der GDI-Konferenz «Prävention im Umbruch».

Vision für die Apotheke 2030

Der Gesundheitsmarkt und damit das Geschäftsfeld der Apotheken verändert sich stark. Vier Entwicklungen bestimmen das Verständnis der Apotheke in zehn Jahren: sie wird mehrschichtig, verknüpft, standortunabhängig und vernetzt.