On November 22, the heads of state and government of the G20 will meet in Johannesburg. It is the first summit on African soil and marks not only a symbolic premiere, but also reflects a gradual shift in the global power structure. Under South Africa’s presidency and its guiding theme “Solidarity, Equality, Sustainability” it becomes evident how the Global South is increasingly taking part in shaping global debates and decision-making arenas. The cancellation of the United States’ participation appears emblematic of this new reality: the Global South is gaining a more prominent place in global affairs while the North is gradually relinquishing its long-held status as the unquestioned pace setter.

Joschka J. Proksik

Senior Researcher and Speaker am GDI

As a political scientist with a PhD, he analyses the interactions between geopolitics, economy, society, environment, and technology.

More about the author

Who or What is the Global South?

The concept is not sharply defined and describes less an exact geographical location than a shared historical and economic experience. Most often it is linked to the 134 member states of the G77, founded in 1964 to represent the interests of developing and emerging countries as a collective voice for developing and emerging economies. While some definitions exclude China, others include it. In a broader sense, it encompasses all states that do not belong to the Western industrialized nations of the Global North. Together these countries are increasingly shaping the structure of the world economy and transforming the future of the global order in profound ways.

A New Engine of Global Trade and Growth

For many decades, the global economy was characterized by a division of labor that had its roots in the colonial era and essentially ran along the North-South axis. Countries in the Global South supplied raw materials and agricultural products, while the industrialized economies of the North controlled the processing stages and captured the lion’s share of value creation.

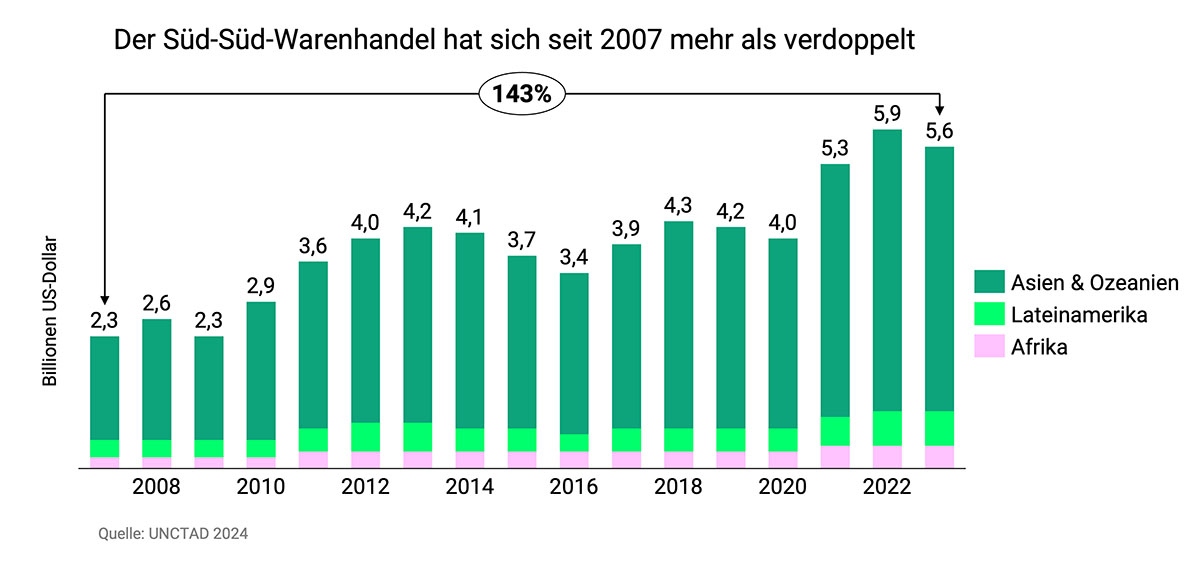

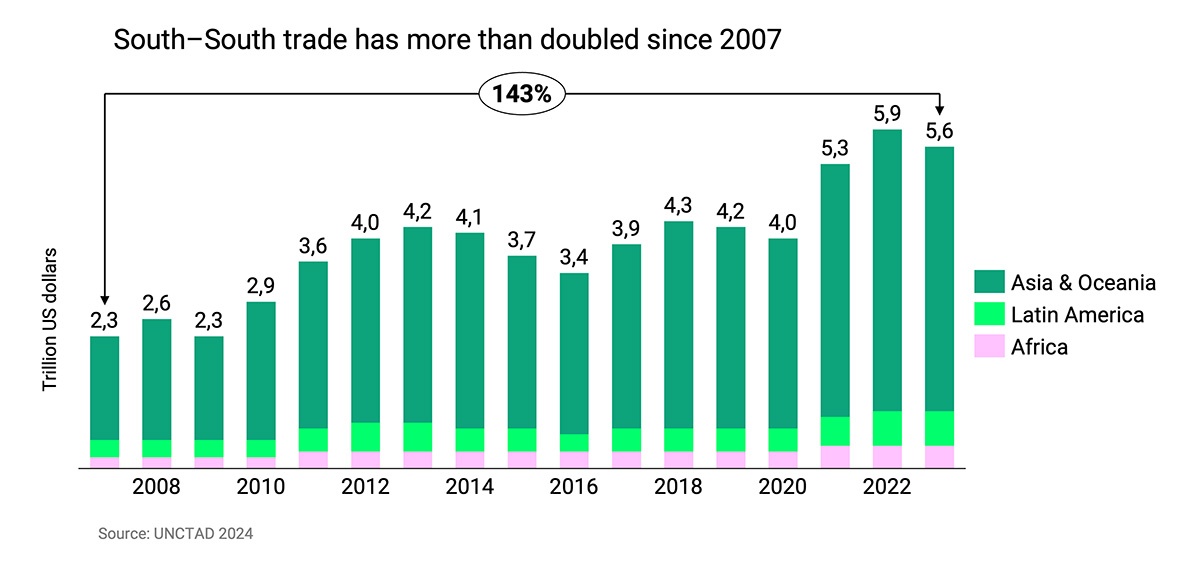

This picture has changed significantly over the past two decades. Since 2007, South-South trade has more than doubled , reaching around US$5.6 trillion in 2023; at the same time, the countries of the Global South accounted for 44 percent of global merchandise exports. Further strong growth is expected in the coming years: trade projections by the Boston Consulting Group predict that trade within the Global South (excluding China) will increase to around US$6.3 trillion by 2033, with a compound annual growth rate of 3.8 percent. North-South trade is also likely to expand significantly, at around 3.7 percent per year, driven in part by new trade agreements such as between the EU and the Mercosur countries of Latin America.

Alongside this quantitative momentum, there is also a qualitative shift: trade within the Global South is increasingly moving beyond traditional agricultural commodities, minerals, and fossil fuels. Emerging economies are tapping into new, more complex industrial sectors. Manufacturing industries such as automotive, electronics, and chemicals are gaining in importance. A growing share of high-tech exports from developing countries now goes to other Global South markets, driven especially by China and other rising Asian economies. Even though many countries remain dependent on raw material exports, new industrial clusters and more technologically advanced value chains are emerging across the South.

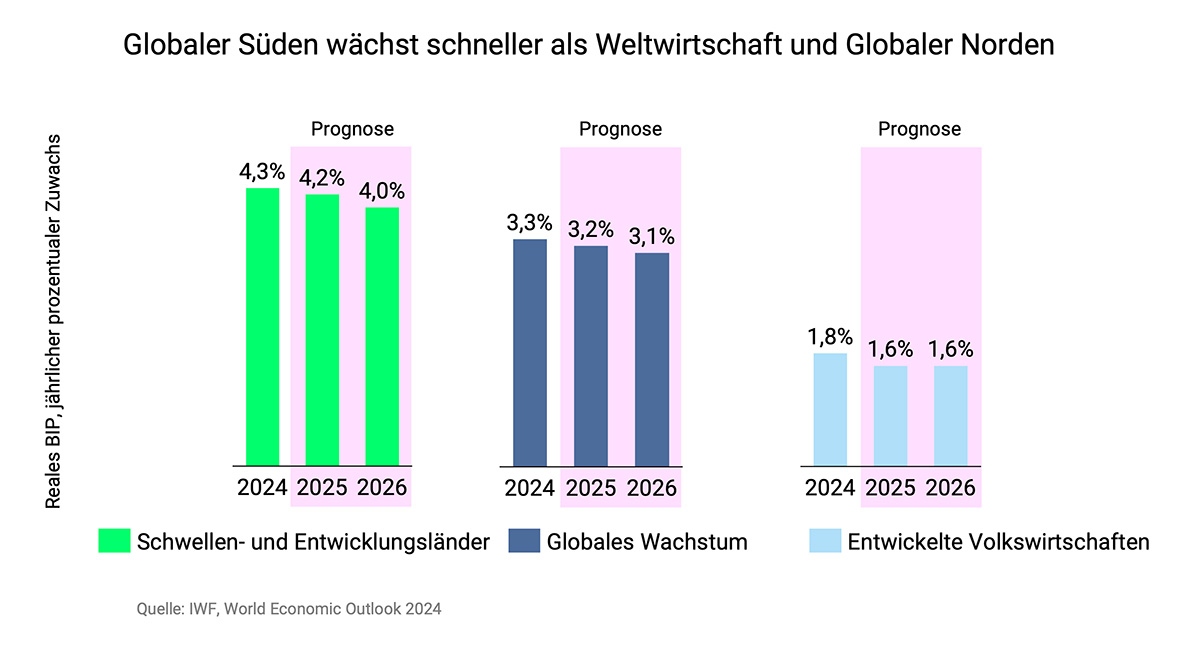

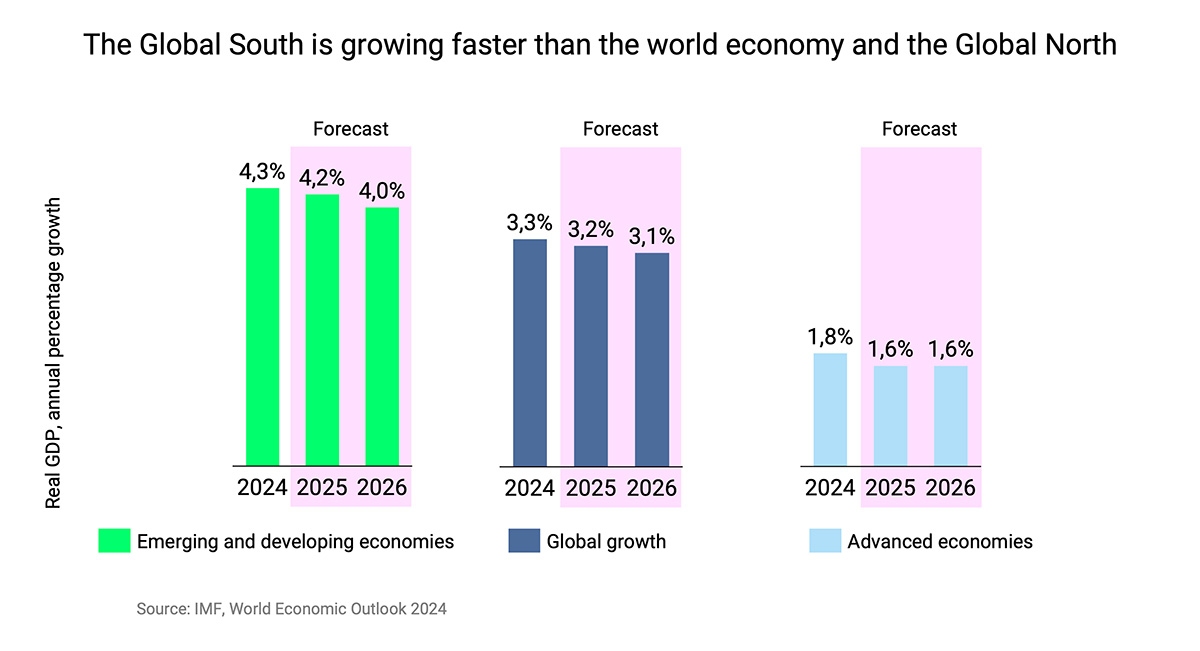

The upturn in trade and industrial production is also reflected in economic development. Global growth dynamics are increasingly concentrated in the emerging and developing countries of the Global South. Adjusted for purchasing power, their share of global GDP already exceeds that of the Northern industrialized nations. At the same time, investment, export shares, and lending from the South continue to increase. The growing importance of regional markets further reinforces this trend. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the average real GDP growth rate in the Global South’s emerging and developing economies reached 4.3 percent in 2024, surpassing the global average of 3.3 percent and well above the 1.8 percent growth recorded in the industrialized economies of the North.

Growth in the Global South is no longer driven solely by China. In 2024, the IMF recorded the highest growth rates in the Central Asian states of Kyrgyzstan (9 percent) and Tajikistan (8.4 percent) as well as in Vietnam (7.1 percent) and India (6.5 percent). Several African countries also achieved strong growth, including Niger (10.3 percent), Ethiopia (8.1 percent) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (6.5 percent). At the same time, significant national and regional differences remain. South Africa, for example, recorded growth of only 0.5 percent in 2024, while Thailand also remained below the regional average at 2.5 percent.

Despite subdued global forecasts, the growth gap between the Global South and the Northern industrialized states will persist. For 2025 and 2026, the IMF expects a large number of Southern economies to continue growing above average. Although the comparatively high growth rates must be viewed in light of many countries’ lower starting levels, the impact is tangible. In many places these economies are undergoing significant economic and societal shifts. New middle classes are emerging, whose increasing consumer spending and growing demand are contributing ever more to global economic activity.

Rising Middle Classes

The economic upswing of the Global South is increasingly reflected in people’s living conditions. In 2023, the world population exceeded four billion consumers for the first time – people who spend at least US$12 on consumption every day. According to estimates by the World Data Lab, their number is expected to increase by another billion by 2031.

The countries of the Global South, especially in Asia, are at the center of this development. Projections for 2024 assume that China and India will account for 81 percent of the global increase in new consumers, with India expected to take the lead for the first time with around 34 million new consumers compared to China's 29 million. Other countries in the Global South, such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Pakistan, Brazil, Nigeria, Egypt, Turkey, Thailand, and Mexico, are also expected to add more than one million new consumers each.

STRATEGIC FORESIGHT

For our client Switzerland Global Enterprise, we developed an AI-enabled tool that allows the GDI Major Shifts to be analysed across industries and markets. This work generated sector-specific implications, emerging challenges and strategic recommendations – for example regarding the rise of the Global South and its impact on Switzerland’s export economy. Our Strategic Foresight team also supports organisations in translating global trends into actionable insights.

Not only is the number of new consumers increasing, but so is their purchasing power. More and more people in the Global South have steadily growing incomes that open up opportunities for consumption and investment beyond basic necessities. What is defined as a threshold of twelve US dollars per day merely marks the entry into a consumer class that in many places is increasingly developing toward a stable urban middle class.

According to a study by consulting firm Oxford Economics, the number of middle-class households (with an annual disposable income of US$20,000–70,000) in emerging and developing countries is expected to nearly double over the next decade – from around 354 million in 2024 to an estimated 687 million in 2034. By then, nearly half of the global middle class will live in China. At the same time, India’s middle class is also expanding rapidly and may more than double in the next five years.

Beyond these two Asian giants the strongest growth will continue to come from the Asia-Pacific region. Vietnam in particular is projected to see the most rapid expansion of its middle class. In Latin America, the middle class is expected to grow as well, though at a more moderate pace. Brazil and Mexico will likely have the third and fourth largest middle class populations in the Global South by 2029, while countries such as Chile, Colombia, and Peru show significant growth potential. Despite persistent economic challenges, Africa too is expected to see noticeable middle-class growth in key economies, particularly in Egypt and South Africa.

Growing Political Confidence

The rising economic strength of many states in the Global South is increasingly reflected in their political posture. Countries such as China and India pursue their interests with growing assertiveness and have made it clear that they will no longer simply subordinate themselves to the established global order. Yet even beyond these two heavyweights, a new political mindset is emerging across much of the South. An increasing number of countries are pursuing independent foreign policy positions. In many cases, this quest for greater independence translates into a political pragmatism that seeks cooperation without binding itself permanently to any one camp.

At the same time, many countries are becoming increasingly aware of their own strategic importance. Many possess significant deposits of critical raw materials and aim to use these resources as political leverage and to accelerate domestic development. Chile, Indonesia and Zimbabwe, for example, are demanding that part of the value added from mineral processing remain in their own countries – a model that is likely to catch on if successful.

This growing independence in foreign and economic policy is also visible in reactions to geopolitical conflicts such as the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. Many states now refuse to automatically follow Western positions and instead articulate their own standpoints.

Despite this fundamental change, Southern countries do not act as a unified entity. They differ markedly in their interests, geopolitical and security perspectives, economic conditions and historical experiences. What unites them is a shared pursuit of political sovereignty, equal participation and greater influence in global institutions. The G20 summit under South African leadership marks another small but visible step along this path.